As a part of my internship with Philanthropiece, I was lucky enough to sit down with our wonderful founder, Libby Cook, to talk about social entrepreneurship, capitalism, corporate social responsibility, and her experience transforming Wild Oats from a few small, local grocery stores into an internationally-recognized, public company. Here are five important lessons I learned from her.

As a part of my internship with Philanthropiece, I was lucky enough to sit down with our wonderful founder, Libby Cook, to talk about social entrepreneurship, capitalism, corporate social responsibility, and her experience transforming Wild Oats from a few small, local grocery stores into an internationally-recognized, public company. Here are five important lessons I learned from her.

Entrepreneurs start early.

Libby’s journey as an entrepreneur began at the age of eight, when she held a carnival for friends and neighbors and donated the proceeds to muscular dystrophy research. She walked around her neighborhood to knock on doors and hand out fliers to let people know about her event. When the day came, it was met with remarkable success. Libby raised $300, which equates to around $3,000 in today’s dollars. Her journey as a very young entrepreneur doesn’t stop there, though. Libby also worked as a newspaper saleswoman, earning a percentage of the cost of each subscription she sold. She scoured the neighborhood until she had hit every single house. Then, when she was 12, Libby got a job at a marketing firm, where she was responsible for collating responses to surveys. These jobs, Libby says, involved a lot of freedom and responsibility and allowed her to gain the confidence to experiment with new ideas and learn how to change her approach when things weren’t quite right. “Part of being a successful entrepreneur is being able to change directions if something’s not working,” Libby adds.

Grit is a valuable trait as an entrepreneur.

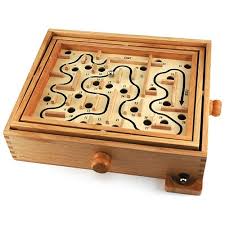

When Libby was eight years old, she discovered a wood labyrinth at her friend’s house. She sat down and worked at it for hours. Once she was able to successfully guide the metal ball forwards and backwards through the labyrinth, she decided she wasn’t done, and added an additional degree of difficulty by attempting to complete the course while maneuvering two balls simultaneously. She stayed up all night working until she got two balls through the labyrinth and back simultaneously. Her friend’s dad, who was then the CEO of IBM, said years later that he knew Libby would be successful; an important precursor to determine how successful a person will be is their ability to stay focused until they solve a problem. This persistent, gritty attitude is a shared attribute among many successful people.

Even after successfully growing a for-profit business like Wild Oats, running a nonprofit poses its own unique challenge.

The operation of for-profit enterprises, as Libby explained to me, is either one- or two-dimensional. The first dimension focuses on generating profit and the second dimension centers around the theme of corporate social responsibility. When operating a nonprofit, the first dimension generally shifts from generating profit to raising funds, the second dimension remains the same, and a third dimension is added to the mix. This third dimension focuses on the cultural differences that must be accounted for when an organization works internationally. For Philanthropiece, this involves developing a deep understanding of communities like Chajul, Guatemala, where the Philanthropiece Scholars program operates, and Baja California Sur, México, where the Philanthropiece Community Banks exist. This added dimension in the international nonprofit sector is essential, and ignoring it could create unintended consequences at best and a devastating impact at worst.

Capitalism doesn’t have to be a curse word.

It’s difficult to talk about business without talking about the economic system in which it operates. The capitalist system is often seen as an evil of society, likely due to what it’s historically been associated with. When people hear the word “capitalism,” many probably also think of corporate greed, inequality, and oppression, and rightly so–but it doesn’t have to be that way. I suggested to Libby that at its core, capitalism is a system that’s predicated on trust among community members. For example, if Bob the Painter’s job was to paint houses, he wouldn’t paint someone’s house if he didn’t think they would pay him for the work he did. He has to trust that he will get paid for doing his job. Libby responded that over the past several decades, capitalism has gained an increasingly negative reputation, and it’s up to today’s businesses and future businesses to move away from that. Capitalism in the sense of making money isn’t bad, because individuals or corporations can use that money to do good – it’s just a matter of incentivizing the primary beneficiaries of capitalism to do so.

Consumers, shareholders, and businesses alike all have a duty to promote ethical business practices.

The responsibility to utilize ethical business practices doesn’t fall solely on the businesses themselves. All stakeholders have a duty to uphold certain values and ensure that businesses are operating ethically. If consumers refuse to buy products or services from a certain company because they believe that their practices are unethical, that provides an incentive for management to change the way they do business. Additionally, if investors refuse to buy a company’s stock due to unethical business practices, that prompts management to act. Finally, employees also have a responsibility to ensure that the business they work for is socially responsible, whether that’s by whistleblowing or standing up to management when they are instructed to do something that goes against their values.

Annie Roberts is currently studying information systems, business analytics, and international development in the Carroll School of Management at Boston College. She is an alumnus of Philanthropiece’s Youth Global Leadership program and served as a YGL Program Intern during the summer of 2016. There’s a very good chance that she knows more about the Denver Broncos than you do.

Annie Roberts is currently studying information systems, business analytics, and international development in the Carroll School of Management at Boston College. She is an alumnus of Philanthropiece’s Youth Global Leadership program and served as a YGL Program Intern during the summer of 2016. There’s a very good chance that she knows more about the Denver Broncos than you do.